Dear Readers

As I look out of my window onto the fields of the rural West of Ireland, in lockdown like much of the rest of Europe and indeed the world, I am thinking in love and solidarity of Slovenia, where I lived for 16 years.

I have been working with Giacomelli media as an English language proofreader and editor for many years, and when the Circular Business Academy was launched, I was delighted when Jurij asked me to contribute to these CBA Conversations.

We are really fortunate that we live on 0.75 hectares of our own land at the end of a very quiet lane only used by the farmer – we are surrounded by nature, and it is the grounding of my heart and soul in these difficult times. We moved from Slovenia to Ireland in part because we had the opportunity to own and manage this small piece of land where we could grow some food for ourselves and the local community.

But now, in 2020, everything, and I mean everything, has changed. Watching the coronavirus begin to emerge in Wuhan, I thought that lockdown was all very well in China, but how could something like that be managed here in Europe? Imagine Dublin or London or Ljubljana with shops closed, public transport barely working, cars and factories silenced. And yet, it has happened.

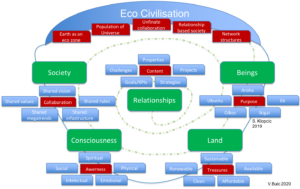

As we adapt, so the initial shock and anxiety has begun to settle. In this time of quiet, many people are realising that we can’t ‘return to normal’, because the normal we had was precisely the problem. Vast overuse of resources, exploitation of nature, pollution, extreme inequality of wealth and social injustice can be argued to have directly caused the situation we are in now, where the need to deal with the pandemic has exposed all the fragilities of modern civilisation. Above all, the disconnection with nature, where men (usually) make decisions affecting millions in air-conditioned boardrooms in skyscrapers high above the Earth – if people are so out of synch with nature, those decisions are based not on living as part of the natural environment, but outside it, seeing it as something to be exploited.

There are so many issues to be considered, and I am looking forward to seeing them explored as part of these conversations. My own ‘cause’ for many years has been the Earth – environmentalism. But traditional environmentalism is a movement that failed, largely because it did not recognise that environmental progress is not possible without social and economic reform. The changes that we need must alter every aspect of society. People who are always worried about money can’t think about anything else; they can’t begin to make their way towards a fairer society and a healed Earth.

The most fundamental issue is food. No matter how big or small the crisis, people are always going to need to eat within a few hours. At the moment the food supplies are holding, but there are major concerns for the months ahead – with people on lockdown across Europe and the world, will harvests be gathered? Will they even be planted, in many cases? Will the problems with transportation mean that food supplies cannot be fairly distributed?

I live on an island now, out on the very edge of Europe. Only about 45 minutes drive from me stand vast cliffs which look across the ocean to north America. Although Ireland’s beef and dairy products are among its major exports, and the country ranks second on the Global Food Security Index list for food security, we still import most of our food and animal feed to this far outpost of Europe, and there is very little storage – we are committed to the just-in-time concept of food distribution. How long will it hold out?

Closely linked to this question is the global destruction of the land and its biodiversity. For decades farmers have been instructed (and subsidised) to remove hedgerows, increase productivity by creating vast fields with no cover for even a mouse, cut woodland and trees, and use pesticides and fertilisers which have broken down the soil and its essential living occupants to an infertile dust. In spite of the idyllic vision of farms as countryside habitats which is still in the common consciousness, most farms today are industrial factories, where inputs and outputs, productivity and investment rule – concerns which have turned many of them into wildlife deserts. The loss of not only biodiversity but also the biomass of native plants, birds, mammals, and especially insects, which form the basis of the food chain, has been truly devastating.

However, there is hope; if we let nature alone, it seems to recover surprisingly rapidly. One place that has turned its story around is Knepp, a large estate of 3,500 acres in the English countryside south of London (the book Wilding, by Isabella Tree, tells its story). Finding that their dairy farm was constantly losing money, 18 years ago they made the pioneering decision to close everything down and allow the land to rewild. The results have been astonishing – insects, birds, mammals and plants have returned with incredible speed, revitalising the landscape and allowing further species to recover. Knepp now makes its living from eco-tourism and the sale of organic wild beef and pork from the animals that roam freely across the whole estate .

In biodiversity lies resilience – there is evidence that it was our own plunder and destruction of the natural world that caused the pandemic in the first place. Diverse, species-rich habitats provide sustenance not only for the beings that live there, but for humans too. Regenerative agriculture (http://www.regenerativeagriculturedefinition.com/), which rebuilds the soil at the same time as growing crops, and small organic farming must be supported and increased at local, national and international levels. It has been found that the use of wide hedgerows and strips of native wildflowers between crops can greatly reduce the requirement for herbicides, pesticides and fertilisers. Leaving unused land aside for nature to recover can have enormous benefits even if only at a small scale.

In Slovenia the practice of growing at least some of your own vegetables is still widespread. In Ireland it has largely died out, though it has been making a comeback, and in the current lockdown, increased demand has meant that many online seed companies have sold out of their stocks. Ireland’s land has a poor reputation for growing vegetables, but last year I was able to grow sweetcorn, tomatoes and cucumbers in our small polytunnel, as well as peas, potatoes, cabbages, onions and garlic outside. This year I hope to grow a lot more, with the intention of not only eating it ourselves, but also sharing it with our local community. Local food cooperatives and collaboration between amateur and professional growers could greatly reduce our dependency on imported food, which is often produced in a way that threatens the local people in countries far away, to say nothing of the impact on climate change of food transported around the world.

‘Dig for victory’ was a famous WWII slogan in the UK; with the pandemic being our generation’s ‘war’, it might be time to revive the idea. The supply of food is going to be crucial in the months and even years ahead – the more we can improve our food security, in Slovenia, Ireland and throughout the world, the better.

Justi Carey